CDC’s review of the epidemiological information on the recent Salmonella Senftenberg peanut butter outbreak indicated that five of five people consumed peanut butter and four of the five consumed the same brand before becoming ill. While this provided little doubt as to the source, it wasn’t the end of the story. Rather FDA’s whole genome sequencing (WGS) analysis further revealed that the strain that caused illness in the current outbreak also matched a 2010 environmental sample from the plant.

Taking that analysis one step further, TAG input the isolate information into the NCBI Pathogen Detection tool and found that there were nearly 500 isolates in this cluster impacting an array of foods including chicken, pistachios, and leafy greens with some going as far back in time as 1987 and others traced as far away geographically as an irrigation canal in Chile. To connect outbreaks, the NCBI Pathogen Detection tool integrates bacterial pathogen genomic sequences originating in food, environmental sources, and patients. It quickly clusters and identifies related sequences to uncover potential food contamination sources, helping public health scientists investigate foodborne disease outbreaks.

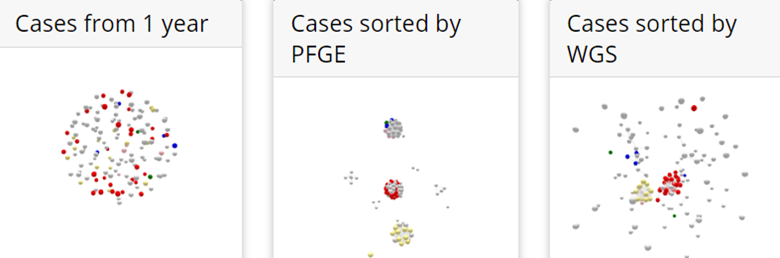

WGS has significantly improved the ability to link outbreak sources across time and geography because it provides a much more detailed DNA fingerprint. A good example of how the technology works is shown in a CDC case graphic:

The CDC graphic focuses on the 149 cases of Salmonella Enteritidis in 2018. Because finding outbreaks is much easier and faster if they can be sorted from non-outbreak cases, the graphics depict the two separately with outbreak cases as colored dots and non-outbreak in gray.

- Although PFGE correctly sorts outbreak cases (center graphic), it doesn’t sort out all the non-outbreak cases, complicating the investigation.

- The third graphic not only shows how WGS more closely clusters the outbreak cases, with non-outbreak cases not connected, it shows how separate outbreaks were linked. The red cluster depicts that what was originally thought to be two separate outbreaks – of two different restaurants in two states – were actually part of a larger outbreak, also involving several patients who had not been to either restaurant.

So once epidemiologic data suggested the cause of the outbreak to be shell eggs, WGS verified that the DNA fingerprint of a Salmonella isolate found in implicated eggs matched the outbreak, confirming the attribution and leading to a nationwide recall.

However, it is always important to link the WGS findings with the epidemiology. Just because a person is sick with the same strain of Salmonella as was found in a production facility, it does not mean that the sick person acquired their illness from food produced in that plant.

Which brings us back to the peanut butter recall. The WGS match of the current strain found with that of a 2010 environmental sample from the same plant likely indicates that a resident strain exists. While the food industry continues to be hesitant to use WGS fearing its ability to come back to haunt them years later … as has this 2010 to 2022 linkage, the technology can be used to your benefit, particularly when a resident strain exists. There are certainly many other historic examples just like this one, and increasingly food companies are starting to question how to ensure they do not have a resident strain of either Salmonella or Listeria monocytogenes.

As we stated in an October 2021 Insights article, it is the very same facts that haunt a facility that can save them from a massive recall, extensive consumer illness, or even deaths, by detecting a pathogen sooner or identifying it as resident strain – before the FDA does. If a resident strain were to be detected in your plant due to an FDA inspection and WGS analysis, your entire Environmental Control Program comes into question, along with any products made during the time frame of the resident strain.

Given all this, why would you not seek to avoid such regulatory scrutiny and action by using the best technology available to detect pathogenic contamination, particularly any which has taken up residence in your plant? Given the proven benefits of WGS on food safety and public health, it just makes sense for consumer and brand protection.

One of the main answers as to why companies do not undertake more WGS of in-house strains is fear of regulatory discovery. There is a widespread fear that if you find a resident strain in your plant, the regulators will discover this fact during an inspection and then there will be significant consequences. But we have this backward – the fear of regulatory retribution for doing the right thing of looking for resident stains is actually an impediment to better public health.